Can you withstand the doom? Twenty-five years after its release, Charlie Leach (@YungBuchan) looks back at Earth’s classic debut album.

This retrospective was heavily informed by the article “The Unbearable Heaviness Of Being” on Seattle newspaper The Stranger. To find interviews with people involved with the making of the album and a musician heavily inspired by the album, please click here.

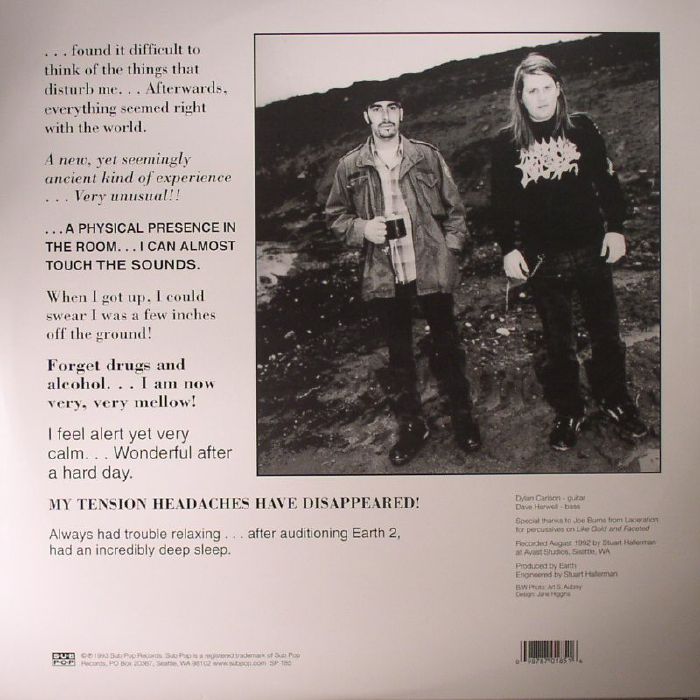

Twenty-five years ago, Earth 2: Special Low Frequency Version was released on Sub Pop records. Harking from Seattle, Dylan Carlson, and Dave Harwell made a record that had little immediate impact on the music world at the time. Coming in an era where peers such as Nirvana had a monumental impact on popular music, a record such as this could have been another small creative release that dissipated into the ether.

Its creation was also fairly small-scale. Though made on a small budget with limited time in the studio, Carlson described the recording process as quite simple; they had already played the first two songs live, so needed no real warm-up time to start recording. Studio engineer for the record Stuart Hallerman also remembers the process as an easy one, describing the recording sessions as having a “very relaxed vibe“. In spite of this, Carlson has since said that if he could record the album again, he would go about it with a totally different method. He states that they wanted a sound as loud as their live shows, but how they set up the mics and amps was flawed, and actually (in his opinion) hindered the overall sound. But for him and Harwell, they were two young musicians who were happy to have studio time that they were being paid for, and so brought their youthful energy and desire into this recording process.

Without previous knowledge of the album, the prior description could conjure images of a young band of the nineties that created an energetic rock album, filled with sharp guitar melodies, rasping vocals, and tight drumming. This is no such album. In fact, this album feels like it takes solace in sheer being the total opposite. This is an album that swamps the listener from the first moment it is played. Hallerman suggested that at the time, Earth’s main mission statement was to out Melvin the Melvins. In comparison to this album, the Melvins are blissful.

Though really intended as an album-long piece due to recording limitations at the time, the album was divided into three parts. Seven Angels, the opening track on the album, commences the album with thunderous, bleeding guitar and bass distortion. This album is not a typical metal album to be born out of the nineties; this album is a drone metal album, and Seven Angels buries that fact into the listener’s eardrums within the first ten seconds. Eventually, a doom-metal inspired guitar riff stomps into the forefront of the song. Taking many cues from Black Sabbath (of which it is rumored Earth took their name from), this slow, meandering riff permeates Seven Angels for its whole fifteen-minute runtime. The riff exudes dread, never firmly resolving itself, building and building over its mammoth run time. After a few minutes of the riff, the song moves out into an incessant, distortion-filled drone. Repeating several times over the course of the track, there is no real rest-bite, and leads to a sense of nervous anticipation and paranoia as to when the riff will come back. The drones here are mainly provided by a sludgy bass line, again soaked in reverb and distortion, but also a distortion that pans and filters around the song, building a cacophony of noise. Even when the “melody” of the song is absent, this song leaves no room to breathe, in no short part due to this droning bass.

Drone is a word used a lot to describe this album, and with good reason. Like all good drone and ambient music (and unlike your average Bandcamp laptop producer), repetition on this record is not wasted; this is a sound that evolves. As Seven Angels oozes forward, the distortion moves with it. More elements of noise permeate the latter half of the track. Additionally, the distortion itself seems to grow in volume and in presence, adding a high tinnitus-inducing ring. There is no room to escape from this album, it burrows into the listener’s brain, allowing enough time to become the only thing present in the mind. This is a contrast to Earth‘s later work. In the same interview as referenced above, Carlson states that Earth 2 is a very claustrophobic sounding album, and if it was recorded now it would be something he would give a lot more and space between the sounds. Though he might look back in slight remorse on this aspect of the album, for many, the all-encompassing claustrophobic nature of the album is one of its true selling-points.

Seven Angels smoothly transitions into Teeth Of Lions Rule The Divine. The louder drone remains on this track, but the guitar riff changes to a more foreboding melody, a melody that gains volume and begins to swamp both channels in the mix. A melody that begins to wriggle into the ear canals, finding comfort in the murky depths. As this riff trudges along, the droning bass begins to gain traction, a white noise second layer beginning to develop over an already excruciating, despair-inducing tone. Not to be forgotten, the guitar riff takes a moment to regain the listener’s attention (if it ever managed to escape it in the first place), gaining a somewhat higher pitch (for this album) to wail into the eardrum. Not to be outshone, the bass swoops into the picture, sound coming in like a tide to the shore, slowly building and building before crashing into existence. As might be clear by now, this album is not great at parties.

Teeth Of Lions Rule The Divine maneuvers into another explosive riff by allowing a rattling crunch of distortion to fill out the song. Then, it announces itself with another Sabbath-inspired thunderous riff, with a chorus of drone and noise to provide the staunch foundations. At the halfway point of a near thirty-minute track, this comes as a somewhat pleasant surprise. Those pleasantries don’t last long. Carlson plays and plays with this riff, allowing it to scream out in pain, to wail in disgust; this is a riff that is exploited for all its worth, raining down its blood-lined tears onto a sea of distortion and sorrow. The murky bass crashes onto the shore and retreats throughout this second movement, allowing a minuscule amount of room for the monstrous guitar riff to truly embed itself into the downtrodden areas of the soul. The white noise found earlier periodically shudders in, punching itself on top of the omnipresent bass drone.

The track eventually fades into the final grand opus of the album, Like Gold And Faceted. The final roar of Earth 2 slings one final surprise into the mix: percussion. Though fairly hidden in the mix, the occasional cymbal crashes add a ritualistic feeling to this final track; this is the last moments, the time to end it all. Of course, a never-ending drone fills the beginning of this track. Slowly building in stature, the absence of any melody is the perfect recipe for fear. At thirty minutes (the longest of the three tracks), this particular drone is an all-encompassing behemoth, slowing stomping its way throughout its epic run-time. Small attempts at melody are made in this opening period, but they are swiftly dealt with, being immediately swamped by new layers of distortion, or new layers of noise. An occasional ring of guitar swims throughout the waves of drone, all while the crash of a cymbal fights for acknowledgment. As the track moves, the cymbal becomes louder, smashing more assertively into the middle of the mix, while a reverse cymbal is used to wash over the whole of the track. This washing is aided by more white noise, at this point an expected accompaniment of the Earth 2 experience. Before the brain has realigned itself with its own sense of self and being, the track is already halfway through, yet there is still no melody.

An absence of riff really pushes the grand statement of this album: this is not a run-of-the-mill metal album; this is an album that pushes the idea of songwriting and performance to its most minimal extreme. As the Like Gold And Faceted slowly fades out into nothingness, so to does the almost meditative-like state the brain inhabits when listening to this album. For an album made by young, relative newcomers to the music scene at the time, this is an album that defies age or time, more an album of never-ending being, which makes its influence in the world of music all the less surprising.

Stephen O’Malley of Sunn O))) recounted his first experiences of listening to the album at nineteen, and it being the gateway into minimal and experimental music. For him, this album is a tower in the music world, and who is to argue? Though made from a humble context, this album is anything but. This is a wandering behemoth, and twenty-five years on is a vastly important classic for metal and experimental music.